Building a ‘world car’ isn’t easy. What might be viewed as a delicacy on one side of the planet could be considered bad taste on the other. To appeal to all palates, there’s a danger that the outcome might be too vanilla. Overwhelmingly competent, but devastatingly dull. Ford needed the Mondeo to be so much better than dull; competent wouldn’t be enough.

Which might explain why Ford allocated a massive $6 billion budget to the CDW27 project, comfortably dwarfing the £1bn it spent on the lacklustre Mk5 Escort. For added context, that’s just $1bn short of the then-record $7bn lavished by General Motors on the W-platform (GM10) project. Spending the big bucks doesn’t guarantee success but having been caught out by penny-pinching and a general sense of ‘that’ll do’ with the Escort, Ford needed to build a car that could breathe new life into an ailing business. Around 10,000 job redundancies, short-time working, declining sales and lost market share had hit its European operations, while life was little better in the US. Despite selling six of the twelve most popular cars in America, and running factories close to capacity, its car business was operating at a loss. The Mondeo had to be good enough to spark an immediate reversal in fortunes, while laying the foundations for future growth and prosperity. No pressure.

A significant chunk of the Mondeo budget was spent on the development of new engines and transmissions: four-cylinder Zeta (later renamed Zetec) engines designed and built in Europe, a 2.5-litre 24-valve Duratec V6 assembled in Cleveland, Ohio. The cost of these engines would be offset by their use in other cars, and as highlighted by the Escort, their introduction was long overdue. Ford had form in launching cars with dated powertrains. The Escort was the most recent example, but the Sierra was similarly hamstrung by ageing engines and the wrong architecture. The late, great Richard Parry-Jones, at the time employed as a product planner, had urged Bob Lutz, the then-Ford of Europe president, to make the Sierra front-wheel drive, but his lobbying fell on death ears.

Parry-Jones’s influence on the Mondeo cannot be overstated. Appointed the car’s executive engineer by John Oldfield, Ford of Europe’s vice president of product planning, the Welshman was there at the earliest stages of development. He left the project in 1988 but returned in 1990 to take on the role of chief vehicle engineer at Ford of Europe. His timing was impeccable. Five years earlier, Ford had highlighted the Honda Accord as the car to beat, but the all-new Nissan Primera (Infiniti G20 in the US) had set the bar even higher. Ford, still reeling from the response to the new Escort, was forced to listen as Parry-Jones pinpointed the areas in need of focus. As Steve Saxty explains in Secret Fords Volume Two, ‘power steering was made standard, allowing the suspension geometry to be changed so that the handling was more benign and engaging. Every control weight was examined for consistency of feel and the car’s on-track performance and on-road smoothness validated by Jackie Stewart.’

According to Fortune, the changes cost $200 per car, and you wonder if Ford would have been so keen to open the cash register without the backdrop of the Escort. Louis Ross, vice chairman of Ford Motor Company, who oversaw the project as international head of operations, was quoted in Fortune as saying: ‘Nobody likes spending the money, but this was a decision that [Ross] Poling [Ford CEO] and everybody shared in. It wasn’t the elves in the back room. The question was, do you want to put your €200 per car in up front, or put it in after like we did on the Escort?’ A car described by Autocar & Motor as, ‘average at most things and truly terrible at others.’ Is it any wonder why Ford was so happy to listen to Parry-Jones?

The eleventh hour changes shouldn’t mask what had been a herculean effort to create an Anglo-American world beater. No fewer than 400 prototypes (240 in Europe and 160 in the US) were built before engineering sign-off in February 1992, a record number for Ford. A total of 150 crash tests, each one costing $300,000 (£200,000), were conducted during development to meet and exceed current European and US safety standards. It was, at the time, the most crashworthy Ford ever, with full-frontal impact tests conducted at 35mph rather than the regulation 30mph. A standard-fit driver’s airbag was a first for its class, while high-spec models came with traction control – a first for Ford of Europe. Anti-submarine seats, seat belt grabbers and pretensioners, ABS and side impact bars were other step forwards in terms of safety. Stuff that barely warrants a mention in 2025, but were big ticket items in 1993, especially on a car like the Mondeo.

Safety isn’t sexy, but the Zeta engines made a darling out of Ford’s Sierra replacement. It had been too long since Ford had launched a new car with modern engines, so the Mondeo wasn’t hamstrung in the same way as the Sierra and most recent Escort. There were three 16-valve Zeta petrol engines at launch: a 1.6-litre/90bhp, 1.8-litre/115bhp and 2.0-litre/136bhp. Each one with electronic fuel injection and a catalyst, and built in Bridgend and Cologne. The diesel option was a 1.8-litre turbodiesel producing 88bhp, while the US-built 2.5-litre V6 arriving in 1994. There were two transmissions: an MTX 75 five-speed manual and an all-new CD4E four-speed auto with mechanical overdrive and a choice of economy and sport modes. From the outset, Ford relied on US expertise for the automatic ’box, V6 engine, air-con and power steering, not to mention the nation’s love of cupholders. The requirement for maximum traction in America’s snow belt was one of the reasons behind the shift from rear- to front-wheel drive.

So, it’s odd, if not entirely surprising, to discover that the Mondeo was a relative failure in the US. Ford planned to sell the European version of the four-door saloon in the US as a Ford and modifying it slightly for the Mercury brand. However, when the design was tested in California in 1991, customers labelled it ‘a car of today, not the future’, flying in the face of Ford’s dream of a car to take them into the new millennium. In light of this criticism, the European design team was tasked with creating a unique skin for the US, adding $25m a year to the production costs. Even with the changes, Ford was forced to dial back its sales projections from 250,000 to 100,000 per year, but the Ford Contour/Mercury Mystique failed to replicate the success of the Mondeo in Europe. Smaller and more expensive than the outgoing Ford Tempo and Mercury Topaz, the Contour lost out to the larger and better equipped Taurus, before being replaced by the Focus. It was a similar story in Australia, where the Mondeo arrived in 1996, but lost out to the locally built Falcon and Holden Vectra, along with a plethora of mid-size Japanese rivals like the Honda Accord, Subaru Liberty (Legacy) and Toyota Camry.

It was a different story in Europe, where the Mondeo was deemed good enough to scoop the Car of the Year award in 1994, beating the Citroën Xantia and Mercedes-Benz C-Class. Members of the press were similarly impressed, with Autocar & Motor devoting 32 pages of coverage to the ‘world class’ Mondeo (17 March 1993). A few weeks earlier (27 January 1993), the same mag had crowned it the ‘king’, declaring it the ‘best family car’. A lot has been written about Ford’s quantum leap from the Escort to the Focus, but less is said about the gargantuan difference in quality between the Escort and Mondeo. The gap was so wide, it’s amazing to think that they came from the same company.

Almost everyone was united in being underwhelmed by the styling. Reviewing the car for BBC Top Gear, a bouffant-haired Jeremy Clarkson said it was, ‘not the most exciting car ever to grace this programme’, but was prepared to give credit to Ford for ‘playing it safe’. Writing for CAR, Stephen Bayley said the Mondeo was, ‘neither risky nor pretty’, before summing it up as ‘rather plain’. Having been stung by the response to the ‘jelly mould’ Sierra, which left its blue-collar loyalists feeling a trifle upset, Ford wasn’t going to make an Eton mess of the styling. Fancy desserts have their place, but who doesn’t love a big helping of bread and butter pudding? The GLX wheel trims were like having your pud served with a dollop of clotted cream. It’s not often that a set of trims can upstage a set of showroom-friendly alloys, but the Mk1 Mondeo GLX was arguably fancier than the Mondeo Ghia.

Six years earlier, project director John Oldfield ordered four full-sized models for review at Ford’s 1987 design conference, sourced from Ghia in Turin, Ford’s California Concept Center in San Jose, and the design studios in Dearborn and Cologne-Merkenich. Four glassfibre models were tested in market research clinics and at the conference, with the Cologne chosen as the basis for the next stage, with input from the Dunton studio in the UK and the other proposals. What followed was a complex and drawn out process, culminating in the creation of the ‘4H’ in September 1988, which was all but approved in March 1989. The ‘5H’ (five-door hatchback) was created for Europe, along with the ‘Wagon H’ (estate), neither of which were sold in the US. Picking a nose was tricky, not least because Ford didn’t have a corporate face. The oval grille didn’t appear until the middle of 1991 but would become Ford’s face for years to come. Plans for a three-door hatchback and two-door coupé were shelved, with Ford choosing to concentrate its efforts on the Mazda-based Probe.

Was the Mondeo really that bland? In a test against nine rivals, Autocar & Motor said: ‘Those who have accused it of being bland need either to make an appointment with an optician or buy a better dictionary. There’s nothing particularly unusual about the Mondeo’s shape, but the forward disposition of its glassy cabin, its low waistline and slim snout, the distinctive design of its lights, its superbly clean shut lines and the general absence of clutter are very attractive and set it apart from the crowd. For the most part, the Mondeo is a triumph for Ford’s design department and refreshingly individual.’ Three decades on, the Mondeo has aged better than many of its competitors, with the Peugeot 405 and BMW 3 Series the most obvious exceptions.

‘Beauty with inner strength’ was Ford’s strapline, and although ‘beautiful’ is a stretch, the line highlights the car’s build quality, safety credentials and attention to detail. It’s the little things like the pen holder and tray under the passenger seat (GLX and above), rechargeable torch in the glovebox (Ghia) and cupholders for rear seat passengers. It was also the first European Ford to be offered with optional adaptive damping and traction control (Ghia and Si), which came as part of a package. The Mondeo was also the first 4x4 production car to feature traction control, but the four-wheel drive version was short-lived, and few survive.

Standard features like power steering, central locking, driver’s airbag and an alarm are things we take for granted in 2025, but were the preserve of premium cars in 1992. Air-con (standard on Ghia, optional on GLX and Si), cruise control (optional on Ghia), graphic display module and remote central locking (Ghia), heated seats and electric sunroof (optional on Ghia), were just some of the features that pushed the Mondeo into premium territory. ‘Mondeo beats BMW’, was the Autocar & Motor headline, but the 3 Series would have the last laugh, going on to outsell Ford’s bread and butter (pudding) family car.

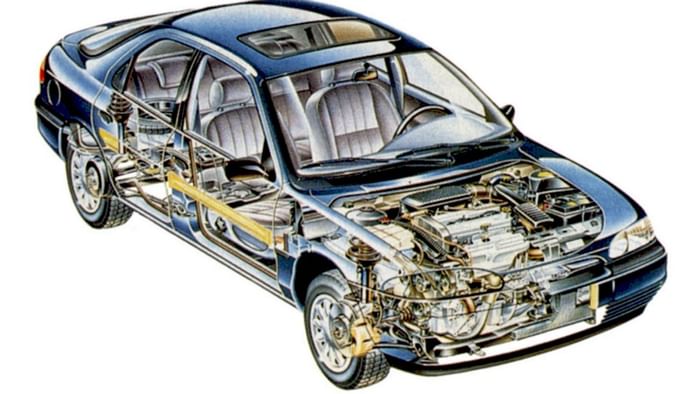

What made it so good? It was a combination of things, but one of the key aspects was the way it felt on the move. In a departure for Ford, both front and rear suspension were mounted on separate subframes, with the aim of reducing vibration, improving strength and minimising assembly time and cost. At the front, the suspension consisted of triangulated lower wishbones, MacPherson struts and an anti-roll bar, while the rear set-up depended on the model. The saloon and hatchback featured ‘Quadrilink’ geometry with passive rear steer, MacPherson struts and anti-roll bar. The estate featured a long trailing arm, three lateral control arms and a separate spring and damper. Ford visited the ends of the world to perfect the Mondeo, from the intense heat of Arizona to the extreme cold of Finland, and on its own test tracks in Lommel (Belgium) and Yucca (Arizona). Nobody worked harder than Richard Parry-Jones, who wouldn’t sleep until his work was done, in some cases quite literally. In 1993, Steve Cropley explained how colleagues would say he’d be in his office in Cologne by 6am, work through to 7pm, drive to Lommel in his Sierra Cosworth, before spending the rest of the night driving prototypes on the track. Parry-Jones tested cars like the Mondeo to the limit to make sure it was as safe in the hands of a parent on a school run or a Little Chef loyalist on the way back from a sales conference, as it was with a would-be Jackie Stewart at the wheel.

Was it better than its Japanese rivals? Almost certainly. Testing it against the Toyota Carina and Nissan Primera, Autocar & Motor said: ‘The result is a car which wins this test, not by blinding its opposition with flashes of brilliance, but by simply being the best car. It dominates in many areas, especially its chassis and brakes, build quality and safety features.’ Like many reviews, the mag criticised the rear legroom and fuel consumption, but these were addressed for the facelifted Mondeo of 1996. What Car? deemed the original Mondeo good enough to name it Car of the Year in 1993, labelling it as ‘a car with quality to match a Nissan Primera, handling and ride to match a Peugeot 405, an interior design to beat a Vauxhall Cavalier and refinement to top the lot’. It remained the benchmark for successive generations, although its popularity waned as buyers chased the perceived benefits of a premium badge. The last Mondeo rolled off the Valencia production line in March 2022 – another victim of the SUV and crossover craze.

A 3000-word article (yes, it really is that long) isn’t enough to tell the story of the Mk1 Ford Mondeo, so you’re encouraged to check out Steve Saxty’s Secret Fords Volume Two and Mondeo: The Story of The Global Car. Its ubiquity and supposed blandness mask a surprisingly innovative and technically interesting car. UK sales hit 88,660 by the end of the first year, and although the Mk1 never hit the top of the annual sales chart, it was the top seller in December 1993. Second in 1994 and third in 1995 and 1996, when the facelifted Mondeo hit UK showrooms. Richard Parry-Jones grew in stature, while the Ka, Puma and Focus cemented reputations for best-in-class ride and handling.

The last word should be given to Andrew Frankel, who said this following a road test in 1993: ‘If I could give you only one reason that best explains why the Mondeo should not be mentioned in the same breath as the Sierra, or, indeed, any other mainstream Ford in its recent history, it is this: engineers, not marketing men are responsible for this car; true enthusiasts who know everything about how to design a car and almost nothing whatsoever about how to sell them.’ Richard Parry-Jones was a true enthusiast, which is why the Mk1 Mondeo was a truly great car.

This article first appeared in issue 15 of Classic.Retro.Modern. magazine.