The roar of a V6 engine, a swerving Probe 24v, and a massive accident in the mirrors – as Robert Palmer’s "Addicted to Love" plays. A far cry from the opposite lock shenanigans of The Professionals, but this was the caring, sharing nineties, and Dearth of a Salesman’s opening frames had made its feelings clear.

Gareth Cheeseman’s antics couldn’t have done the Probe any dirtier: barely a year into the Probe’s UK life, its card was marked. His blue car was a dead ringer for the launch campaign Probe (advertised with the “Go Your Own Way” Fleetwood Mac strapline), and was a foil for his egotism.

Whether or not the Probe was meant to be a new Capri is key to rescuing it from obscurity. That it also played a key role in the Mondeo’s World Touring Car Championship wins in 1993 and 1994 needs repeating.

Most know that the Probe originated in the US, where its predecessor came worryingly close to launching as the fourth-generation Mustang. Profoundly negative customer clinics told Ford what it needed to know, and its 1993 successor (the car we received a year later) carried on in its own right, sold alongside the SN95.

It was a car destined to live in the pony car’s shadow: a sacred nameplate, like the Capri, that Ford dare not mess with. Design chief Mimi Vandermolen had worked on the Mustang II; furthermore, she’d headed up interior design for the 1986 Taurus, the car that rescued Ford in its homeland. The Probe had pedigree – pedigree it couldn’t escape.

Among other things, the name didn’t translate well. For US audiences, the moniker evoked space exploration into uncharted territory: it had also adorned five beloved concept cars, the first of which had used a Mustang ‘Fox body’ platform; Probe III previewed the Sierra’s styling. Vandermolen’s team paid tribute to those cars, but it, like the Motor Trend 1993 Car of the Year Award, mattered little in the UK. ‘Probe’, with much piss-taking, conjured up invasive trips to the doctor (or alien abduction). "When it arrives [in the UK] in the autumn of 1993, will it really be called ‘Probe’? I think not," Jeremy Clarkson asked.

Fords had long exceeded the sums of their parts (the 1969 Capri, in disparaging terms, was an altered Taunus/Cortina with Philip K. Dick body); brilliantly marketed and fun to drive, they packed showrooms and streets. Part of this sell was ideological – Ford wasn’t American, you see. It was British.

But the Probe was Japanese at heart: starting with a second-generation Mazda MX-6, Ford of America repackaged the oily bits to create the Probe. This was bad, somehow, in the eyes of its beholders. Following tests at Zolder and Ford’s Lommel proving grounds in Belgium, UK-market Probes received differently valved dampers.

Both MX-6 and Probe were built side by side in Flat Rock, Michigan, USA, under the AutoAlliance International joint venture, of which Ford acquired a 50 percent stake in 1992 (ironically, the same plant now makes the Ford Mustang).

Usefully, the top-of-the-range Probe 24v (sold in the US as the GT) inherited quite an engine: the 60-degree, aluminium alloy, 2.5-litre, 24-valve Mazda KL-V6. Rouse Sport and Cosworth Engineering, contracted to build and develop Ford’s Mondeo touring car, looked at the KL-V6 with interest: knowing they could use any engine from the manufacturer’s worldwide range (and having realised that, to the rulebook, the four-cylinder Zetec’s valves were too close together, and its bores were too small), the announcement of the Probe was a godsend. Destroked to 2.0 litres, as per regulations, the KL was the right tool for the job.

‘It didn’t have to be a UK car,’ said Andy Rouse, four-time British Saloon Car Championship title winner and founder of Rouse Sport (later Rouse Engineering). ‘[The KL] was very small, and it was quite a light engine, with decent bore size and decent valve size. It was pretty ideal for the job, really. It was good timing that that engine became available, just when we needed it.’

For Rouse Sport, there was no second choice: the bulkier, US-designed Duratec V6 arrived a year too late. An SAE study into its suitability for North American Touring Car Racing in 1996 found it ineligible owing to piston speed limits. Valve angle had to remain standard, too: here, also, the Duratec was uncompetitive (laughs in TWR Volvo 850).

Then, alas, we consider the Capri, and the deep reverence for that car in the hearts and minds of the British public. This was a car that Ford kept on making for us (and us alone) past 1984, rendered critically old-hat by hot hatches (Ford’s own Escort XR3 and XR3i) and front-wheel drive Japanese coupés. Absence makes the heart grow fonder; titles regretted how hard they’d been on the Capri in its twilight.

Ford fans still wanted rear-wheel drive fun. Lots of drivers did. In the USA, the Probe wasn’t their only option – the Mustang was still on sale.

On paper, it sounded perfect: beat the Japanese at their own game by giving Ford fans a front-wheel drive coupé in a fresh set of clothes. In truth, it vacated the market too soon.

Capri fans bought BMW 3 Series coupés instead: those rear-wheel drive cars had the dynamics they craved. A few bought the Nissan 200SX (S14 Silvia) but many deemed it too expensive for the badge on its bonnet.

Uncle Henry was certainly aware of the shoes the Probe had to fill in the UK, its first press release dedicating four paragraphs to what it termed the ‘real’ Capri, and ‘The Capri success story’ having acknowledged the 1962 Consul Classic and the 1964½ Mustang (the latter ‘practically inventing its own market niche […] in the United States’) stopped short of declaring the Probe a Capri successor.

The inference was clear, but in that copy, which made frequent reference to the ‘similarity’ of its suspension to the Mondeo (and the success of the touring car’s incumbent Probe engine), Ford knew it was playing with fire, sheepishly admitting that it misjudged the market:

‘Between 1989 and 1991, sales of sports and speciality cars in Europe doubled as a flood of new European and Japanese products arrived in the market, stimulating buyers once again to look for alternative expressions of independence. To meet this growing demand, Ford began investigating the possibilities of returning to the European sports coupé market by importing the North American Probe.’

The press had no doubts as to what Ford’s new car was, however: the Capri, reprised. The New Ford Capri, Paul Horrell’s report from the Detroit show screamed, in March 1992’s CAR Magazine. ‘It’s not a bad name, Probe, for a sleek and pointy sports car. But “Capri” means so much more […] Ford hasn’t ruled out resurrecting the badge for Britain when the Probe goes on sale here in late 1993.’

Top Gear, at the end of a Mazda MX-6 road test, got straight to the point: the Capri V6 set the template for newer GTs, and that Ford’s soon-to-arrive Probe was the first American-built Ford to be sold in Britain since 1909.

Sending the Probe to Japan meant that other right-hand drive markets would soon be able to buy it, with Jeremy Clarkson concluding: ‘Odd, isn’t it, that the Japanese killed the Capri, and now, thanks to them, it’s coming back.’

CAR, having included a test of a US-market Probe GT on its cover, billed ‘Next Year’s Ford Capri’ in September 1992, pulled even fewer punches in April 1994, when it pitched the recently launched Probe 24v against the Toyota Celica GT, Vauxhall Calibra V6 and VW Corrado VR6: ‘Ford misread the coupé market when it let the Capri die in ’87 without a replacement. Seven years on, its comeback with an American import smacks as much of panic as of expediency.’

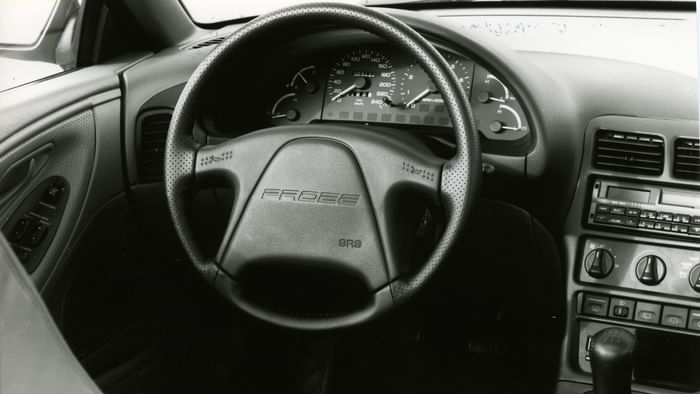

Three years later, Ford would pull the plug. The Probe 24v could outdrag and outhandle most production Capris, but the market didn’t care. It wasn’t rear-wheel drive, it wasn’t macho: it had too much unintended baggage.

‘What have I done? It’s my fault! I parked it there!’, screamed Gareth Cheeseman at Dearth of a Salesman’s end. With a bloody nose (and a reputation in tatters), his Probe 24v in the Saunders Birkdale car park was a battered, unwilling accomplice. Ford’s plan hadn’t worked.

Low residual values and the 2009 scrappage scheme took chunks out of the already dwindling Probe population: many more were fragged owing to immobiliser issues (the very same unit that Ford proudly boasted of in its first UK advert) that Ford dealers couldn’t fix, leaving cars stranded.

The UK Probe Owners’ Club (UKPOC) devised a work-around years ago, saving many more examples from the scales. Most survive today as cherished modern classics, their styling, reliability and pop-up headlights an obvious draw.

Grippy, rev-happy and easy to drive, its dynamics were different to – but no less valid than – the sideways silliness encouraged by V6 Capris of yore. By the end of the nineties, Ford’s front-wheel drive cars were lauded. The Probe arrived too soon to bask in that newfound glory.

A victim of impossible expectations? Yes. A bad car? No.

A Capri replacement? What Ford promised itself and what fans expected differed wildly. Another no. In its own right, the Probe was more than competitive. Ford knew exactly what it was getting the Probe into, and it didn’t stand a chance. It was sold out by the press – the same press that would have delivered a kicking had it brought another rear-wheel-drive Capri to market. Neither Ford, nor the Probe, could win.

Bereft of nostalgia, but no less worthy, time was no kinder to the Cougar (1998-2002), its replacement.

Ford’s current Capri is an electric crossover. In hindsight, was the Probe that bad?

Straight from the pages of Classic.Retro.Modern. issue 35, where the Probe briefly basked in the Capri’s shadow once more.