If Daimler could turn back time, it would almost certainly go back to 1989, when Cher was all hair and fishnets on the deck of USS Missouri. Jumping aboard the Smart project put the German company in danger of being left up a particular creek without a paddle.

Heck, building battleships might have been a more sensible move. According to figures released by Bernstein Research, the then DaimlerChrysler sank about 3.35 billion euros into the Smart project, resulting in losses of around 4470 euros for every car sold. It’s no wonder Ferdinand Piëch was so quick to jump overboard when he took the helm from Carl Hahn as captain of the good ship Volkswagen.

To understand the history of the Smart car, you need to wind back the clock to the 1980s. The self-made millionaire Nicolas Hayek harboured ambitions of building a small car using the techniques he developed as CEO of the Swiss watch business Swatch. Confidence was never a problem for the late Lebanese entrepreneur; in an interview with Time magazine in 1994, he said: ‘I am the creator of products, kingdoms and empires.’ It all sounds a bit Game of Thrones. His self-belief wasn’t without substance, as Hayek is credited as rejuvenating the Swiss watch industry, which had seen its global market share shrink from 43 percent in 1974 to just 15 percent in 1983. Having been approached by a group of Swiss banks, he took control of one-third of the Swiss watch companies, restoring the market share to 53 percent. All without the help of dragons.

The original ‘Swatchmobile‘ was developed in the Swiss town of Biel. Hayek and his team of engineers set out to create a car that was 20 percent smaller than a typical supermini, could fit nose-in to a standard parking bay, cost no more than $10,000, and travel at speeds of up to 90mph. The cars would run like clockwork using petrol, electric or hybrid powertrains. ‘Conceiving a car like this requires a totally different approach,‘ Hayek said in an interview with CAR in 1992. ‘The motor industry was not prepared to take such a risk, but I accepted the challenge, because we at Swatch have the money, the know-how and the right people.’

At that stage, it was Volkswagen and not Mercedes-Benz spending time with Swatch. The proposed car, which didn’t look too dissimilar to the original Renault Twingo, was designed in-house, with Volkswagen and the Engineering College of Biel working with Swatch on the technical side of things. It wasn’t to be. VW’s financial position was far from stable as Ferdinand Piëch took office on 1 January 1993. ‘I wanted to clear my desk of this Swatch business as soon as I took up my post,‘ he said in his autobiography. As Tony Lewin points out in Smart Thinking, entrusting an external company with the development and launch of a new eco car would send the wrong message to his staff. ‘This would have given our R&D people the message that they were incapable of doing it on their own, that we preferred to bring in a Swiss engineer who had a big hit with watches.’ Ouch.

He points to the development of the Volkswagen Lupo 3L as another reason for calling time on the Swatch project. ‘The idea of our own small car with three-litre (94mpg) consumption was already around. It seemed a much better proposition than a two-seater with an absurd wheelbase that couldn’t possibly give enough space for the things that make up a proper car. For me, it was an elephant’s roller skate – not even a practical bubble car.‘ Double ouch.

A lucky escape for Volkswagen, but it’s worth remembering some of the other projects he oversaw during his tenure. The Bernstein Research analysis shows losses of 1.99bn euros for the Volkswagen Phaeton, 1.70bn for the Bugatti Veyron, and 1.33bn for the Audi A2. One man’s elephant’s roller skate is another man’s white elephant.

Hayek would have sensed Volkswagen’s cold feet. The watchman was on the look out for another partner, long before senior execs from VW had hot-footed to Biel to deliver the bad news. There are suggestions that Mercedes -Benz and Swatch held discussions in 1992, but the first official meeting took place in January 1993. In Smart Thinking, the Mercedes-Benz passenger car division boss Jürgen Hubbert is quoted as saying: ‘Before we went to see Hayek I quite naturally did some research into his history. Before we met for the first time I needed to understand his reasons for wanting to go into this venture. He was still working with VW but had the impression it wouldn’t be successful, mainly because the characters of Hayek and Piëch were extremely different – and difficult. So Hayek was of the opinion that he had to stop – and on the other side Werner Niefer [Mercedes-Benz chairman] was pushing to go in just that direction. For me it was surprising to be talking about such a project: we had done some work in that area a few years ago in our research department, but I was still surprised that Niefer wanted to go that route.’

The work went back further than a few years. In 1972, Johann Tomforde, the original head of development and production on the Smart project, wrote a letter to Werner Breitschwerdt, the then deputy director at Daimler-Benz. Tomforde argued that ‘the role played by the contemporary automobile in future traffic systems [would depend on] the automobile’s possible functions as part of a newly designed, optimised traffic system.‘ His project team had developed a two-seat city car measuring 2.5 metres in length and with a wheelbase of just 1.7 metres. The drawings show a one-box design with a short front end, and power sourced from an electric drive system positioned under the seats. Nine years later, Mercedes-Benz unveiled the short-radius car (NAFA). Tomforde and his team of researchers, engineers and designers developed a car with an uncanny resemblance to the Smart. Just 2.5 metres in length, 1.5 metres tall and wide, and weighing just 550kg, the NAFA was powered by a 1.0-litre three-cylinder engine. Thanks to four-wheel steering, the turning circle of 5.7 metres would have been enough to make a black cab driver turn green with envy. The 1972 and 1981 concepts had one thing in common: poor passive and active safety. A lack of protection for the occupants was the Achilles' heel of a small car.

By now, Swatch and Mercedes-Benz were on a collision course of their own. A meeting of minds and, with the benefit of hindsight, a growing sense of destiny. Nicolas Hayek required a new partner, while Mercedes-Benz was in desperate need of new products. It had seen sales fall by 11 percent in three years and had little to offer young and upwardly mobile motorists. Its cars were expensive and driven by either wealthy executives or German cabbies. Getting into bed with Swatch came with the promise of excitement and a greater understanding of young customers.

But first, a dinner date. Hayek and the Mercedes-Benz CEO Helmut Werner had a six-hour meeting at the 1993 Frankfurt motor show, before the companies made an official announcement of their engagement in March 1994. Mercedes knew that it could hit the ground running courtesy of the petrol-powered Eco-Speedster and electric Eco-Sprinter concepts. The cars, designed by Mercedes-Benz in California, were unveiled under the Micro Compact Car (MCC) banner, with Mercedes-Benz taking 51 percent of the business, leaving 49 percent to Hayek and his SMH (Swiss Corporation for Microelectronics and Watchmaking Industries) business. A year earlier, a team of Mercedes-Benz delegates had travelled to Biel to see the Swatch car. Even then, it was clear that the Swatch-Benz marriage would be far from easy. Jürgen Hubbert described the test vehicle, which was based on a Citroën AX, as a ‘small vehicle, hammered together and fitted with a variety of electronic components plus four wheel hub motors.‘ The phrase ‘hammered together’ hints at a deep crack in the relationship, even before the ink was drying on the joint venture agreement. Hayek had visions of a fleet of cheap city cars, produced at minimal costs and as colourful as Swatch wristwatches, while Mercedes-Benz was more concerned about the car’s structure, particularly in relation to occupant safety. There was also a difference in opinion over the source of power, with Hayek’s preference for electric in stark contrast to Stuttgart’s desire for petrol and diesel. It’s quite telling that at a press event held in Sarreguemines, close to the future Smart factory, the direct involvement of Hayek and SMH was rather glossed over. It’s as though Swatch was viewed as a vehicle to make Mercedes-Benz look trendy. Like giving a pair of Nike Air Flight One trainers to the board of directors. The German company had little hope of appealing to the target audience of singles up to the age of 30 and ‘youthful older men and women’, but Swatch knew what made them tick.

Nicolas Hayek was still named vice-chairman of the board at MCC when the Smart made its global debut at the 1997 Frankfurt motor show, but he had sold his shares to DaimlerChrysler earlier in the year. By then, Hayek and Mercedes-Benz had settled their differences over the choice of powertrain, after the Swiss had invited the Germans to a trial driving session on an ice rink in Biel. The all-wheel drive electric car failed the test, leaving Hayek without a leg to stand on. His electric dreams had gone cold.

Design approval was granted in April 1995, before show cars were presented at the Atlanta Summer Olympics and Paris motor show in 1996. Jürgen Hubbert was understandably buoyant as the covers came off in Frankfurt. ‘For many people the car is a symbol of freedom and individuality. As long as this is the case, the desire for mobility will remain. This is the reason I ask not why Smart is coming but how. And today, you can find out exactly how we have managed to turn an inspired idea into reality, just three years after giving the go-ahead to the most innovative compact car in the history of the automobile.’

Lars Brorsen, president of MCC, labelled it ‘quite simply, the city car of the future’. This proved to be rather premature, as the future would have to wait. The MCC Smart hit the headlines for all the wrong reasons in December 1997 when it flipped over during extreme manoeuvring tests. This caused further embarrassment for Mercedes-Benz, after the A-Class had experienced similar problems in the autumn, resulting in the recall of 17,000 cars and a relaunch with ESP fitted as standard.

While the MCC Smart was refusing to stay upright, production was underway at the so-called Smartville factory in Hambach, France. Built at a cost of 830 million Deutschmarks, the factory had capacity for 200,000 vehicles a year, with a Smart rolling off the production line every 4.5 hours. The state-of-the-art factory opened in October 1997 in the presence of French president Jacques Chirac and the German chancellor Dr. Helmut Kohl. If one of the leaders didn’t make a quip about the Franco-German partnership being a ‘smart move’, they should have had a word with their scriptwriters. As an aside, Ineos has purchased the Hambach factory from Daimler for production of the Grenadier 4x4.

MCC attempted to put a positive spin on the failed ‘moose test’. Johann Tomforde left the project in spring 1998, replaced by Dr. Gerhard Fritz of Mercedes-Benz M-Class fame, with the car re-introduced at the Geneva motor show as the ‘Smart optimised’. Lars Brorsen called the decision to postpone the launch by seven months ‘the right one’, as if he had a choice. One Mercedes-Benz executive told CAR: ‘This car will never be profitable, especially after the last-minute changes, which brought the total investment to 1.8bn Deutschmarks. But cancelling the whole programme would have been an even more expensive experience.’

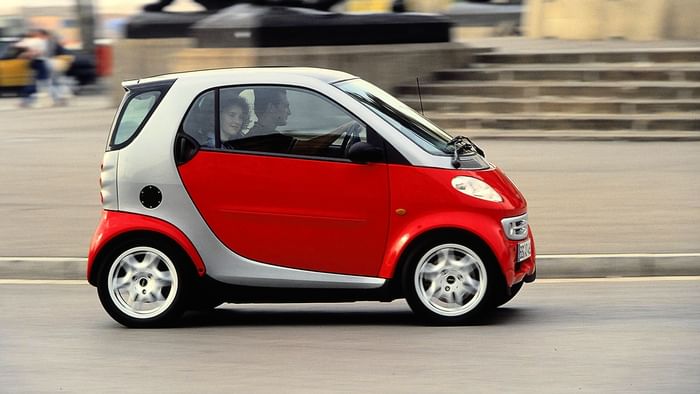

The Smart City-Coupé, as it was now known, went on sale in Europe in October 1998, with the final version looking subtly different to the model shown in Frankfurt. Front axle widened by 16mm to 1286mm, rear track widened by 86mm to 1353mm, and suspension lowered by 20mm at the front and 15mm at the rear. Externally, the City-Coupé was 64mm wider (1515mm) and 18mm lower (1530mm), while inside, the seats were lowered 20mm, with the passenger seat moved back 155mm. As a result, the vehicle’s centre of gravity was a moose-friendly 45mm lower.

The problems with the ‘moose test’ shouldn’t overshadow what was otherwise a thoroughly well-engineered car. Mercedes-Benz was determined to make it as safe as its larger and more expensive cars, so the development of the Tridion safety cell should be applauded. The extremely strong metal frame wrapped itself around the passenger compartment and was supported by a set of crossmembers. Front and rear crumple zones were used to protect occupants in a crash, while even the front wheels were designed to deform in the event of a collision. The sandwich-type construction and raised seat position removed occupants from immediate danger in the event of a side impact, while twin airbags, ABS, self-tensioning seat belts, knee impact bolsters and a collapsible steering column were a big deal on a small car. The City-Coupé also featured an intelligent electronic stability programme called TRUST (Traction und Stability). It wasn’t difficult to spot where the money had been spent.

Mercedes-Benz even developed new turbocharged engines for the Smart project, with the M160 units marketed under the Suprex name. The car debuted with a 600cc engine available in 44bhp or 54bhp outputs, before a larger 698cc unit was installed as part of the 2002 facelift. Diesel and performance Brabus versions also followed, along with a name change to Fortwo. The rest, including the launch of the Convertible, Crossblade and Roadster variants, is history, and a story for another day.

The birth of the Smart car was a long time coming. Given the lengthy gestation period and the opportunities to make different decisions, you’d be forgiven for expecting perfection. It was a hugely ambitious project involving a purpose-built factory, a bespoke engine, a specially developed safety cell and a clever stability control system. To its credit, Mercedes-Benz crammed a lot into a car that was 550mm shorter than the outgoing Rover Mini. But the slow sales were never going to be enough to recoup the huge investment, while even the most ardent of Smart fans would probably admit that the driving experience could have been better. One question remains: was it the wrong car at the right time or the right car at the wrong time?

This article first appeared in issue 2 of Classic.Retro.Modern. magazine.